That JORVIK Viking Thing Podcast

The Coppergate Excavation: Science of the Soil

Preservation is the name of the game on the podcast today. We talk to Ian Panter, head of conservation at York Archaeological Trust, and ask him about how the artefacts were preserved first in the soil at Coppergate and then in the conservation lab. Is there a secret to the soil here in York? How do they conserve 1,000 year old timbers? And just how many things did Jim Spriggs swipe from skips to set up the first conservation lab?

Links for more information:

Barangaroo Boat project

The Mary Rose project

Listen and enjoy, and please consider leaving us a 5 star review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen!

Preservation is the name of the game on the podcast today. We talk to Ian Panter, head of conservation at York Archaeological Trust, and ask him about how the artefacts were preserved first in the soil at Coppergate and then in the conservation lab. Is there a secret to the soil here in York? How do they conserve 1,000 year old timbers? And just how many things did Jim Spriggs swipe from skips to set up the first conservation lab?

Links for more information:

Barangaroo Boat project

The Mary Rose project

Listen and enjoy, and please consider leaving us a 5 star review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen!

Miranda 0:01

In Viking times, a "thing" was a gathering, a place where leaders and warriors could meet and talk. In the 21st century, our "thing" is a virtual place, where history academics and enthusiasts from around the world can come together to share knowledge. I'm your host, Miranda Schmeiderer, and this season, we’re doing a deep dive into the Coppergate excavation. So hold on to your helmets for this episode of That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast!

So far this season, we’ve learned about the excavation itself and the amazing artefacts from not just the Vikings but also the Romans, Medieval people, and Victorians who called Coppergate home. Today, we’re trading our hi-vis vests for lab coats to learn more about the science of the soil and the conservation techniques that our team still use today to preserve these fantastic artefacts. We’ll be talking to Ian Panter, head of conservation here at York Archaeological Trust, who has actually worked on conserving Coppergate.

You might have noticed I said “conserve” and not “restore.” As we talked about in our Viking finds episode this season, there’s a difference between conservation and restoration. In restoration, specialists are trying to bring an artefact back to its original appearance and form, and a lot of times, that means filling in broken parts or adding new bits altogether. For conservation, specialists work to maintain the artefact as it is, so that future generations can see the whole story of the artefact, not just the original creation of it. A lot of times, a particular item is used multiple times in multiple ways. At Coppergate, Roman bricks were re-used during Viking times to line hearths, pottery kilns, and blacksmith’s forges. If we decided to restore these bricks, part of the story of the bricks would be lost. But if we conserve the bricks, archaeologists and visitors alike can learn how Vikings recycled material around them as well as how the Romans made the bricks in the first place. Since we want to know as much of the story as possible, we have a conservation department here at York Archaeological Trust. And of course, the leader of that department is with us today. We actually went over to the conservation lab to chat with Ian for this episode.

Hi, Ian, thanks so much for speaking with us today. In our first episode, we mentioned that it was the soil at Coppergate that preserved these finds. Can you tell us a little bit about what makes the soil so special?

Ian 2:18

Yeah, basically, it is waterlogged. Because Medieval, Viking, in fact right back to the Roman times, settlement at York has been between two rivers, the confluence of the River Ouse and the River Foss. So we've got a lot of waterlogged deposits. And it's the water that gives them the preservation of the organic material. Because if you imagine the waters filling the soil, the voids, the spaces within the soil, the air that's normally there in normal soil is no longer there, it's been replaced by the water. So because you've got low oxygen or no oxygen, then any sort of microbes or bacteria, moulds, things like that, that tend to digest organic material, they no longer live there. So you get fantastic preservation of organic material.

Miranda 3:04

So if it's the water surrounding the artefacts that preserves them, what happens when the archaeologists remove the artefacts from the wet soil?

Ian 3:12

They have to keep everything wet as they're digging down through the layers, and before they say remove everything. So it is sort of having to sort of spray the soil as they're excavating, keep everything wet. If there's anything fragile and vulnerable, then call the conservators in and lift the items, get them into the conservation lab, where we can sort of put them into tanks and containers and keep everything under water. And that will then stop everything, you know from further decay occurring. We may have to use chemicals to try and sort of control biological activity in those tanks while the items are under storage as well.

Miranda 3:49

There's a really great sound clip of someone talking about how Richard Hall was always going around Coppergate shouting "keep that wood wet!"

Ian 3:55

[laughs]

Miranda 4:01

In the 1970s, archaeologists didn't really have a ton of experience preserving items on site. So what techniques did they come up with to prevent further damage to the artefacts?

Ian 4:11

There's quite a few interesting techniques, actually, there's been a sort of a range of processes that have been used from a sort of creosote that we used to apply to the fences before we suddenly realized it was toxic. It's a banned item now, you can't sort of coat your fence in creosote because I think it gives you cancer, but there are a number of log boats that were preserved that way. But we were experimenting with a technique called acetone rosin which was highly dangerous, because it involved heating the acetone to a high temperature to get the rosin, which is a natural tree resin. It's like amber. So you need to get that into solution, in the acetone, and the only way to do that is to heat it. And the flashpoint of acetone is about 17 degrees centigrade [62 degrees Fahrenheit]. So you have to be very careful, because it could explode so we had a facility in our old laboratory, which was designed to do that. But all our lights and all our switches have to be spark proof because with the volume of acetone we had, if you, coming in the first thing in the morning, switch the light on it could go boom. So at that time we're the back of Peter Addyman's garden in effect, so he obviously didn't want to lose his house. So we were sort of using those sorts of techniques but at that time, I guess in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s, the Scandinavians were experimenting with PEG wax on the Viking longships and and such things so so we really sort of followed what they were doing and adopted the techniques

Miranda 5:46

Is that what we still do today then?

Ian 5:48

We do, that's right. Yeah. So what we started off doing back in sort of, I guess, the early ‘80s with all the Coppergate house timbers there on display, those were all treated with polyethylene glycol that we took those up to around about 80, 90% PEG wax and then we slowly air dried them. In actual fact, they were slow air dried actually within Jorvik One because the timetable for getting them off site, getting them conserved, and on display, in the first Jorvik was quite tight. Jim and his team at that point, had to take them out of the treatment tank, take them down to Jorvik and put them on display and let them slowly air dry there. We did some monitoring of it and there's very little movement of the timbers. Wow. It was actually quite encouraging. But the process we use now is freeze drying. And you actually use less polyethylene glycol wax when you're freeze drying. So freeze dried timbers look more natural, they've got a sort of brownier colour, whereas you notice the Coppergate timbers which are air-dried, they look black and feel quite waxy.

Miranda 7:00

In our first episode of this season, Tales from the Trenches, we heard Jim Spriggs talk about setting up the first conservation lab at Coppergate. In case you missed it, here it is again:

Jim Spriggs 7:10

I arrived in York, one gloomy October day in 1972 to take up my post as conservator at the newly founded York Archaeological Trust with very little idea of what to expect. I was familiar with excavations, having done lots of digging previously but had no experience in how to set up a laboratory and little idea on how to staff and run one. My first permanent conservation lab was two small basement rooms in St. Mary's Lodge on Marygate which were dark, damp and prone to flooding. But I and my gradually expanding staff and students managed to survive down there for almost eight years. Equipment was begged and borrowed from various places, including some lovely solid mahogany benches originally from the food department in Woolworths. The waterlogging at Coppergate had caused the spectacular survival of the original timbers and wattle and daub that made up the buildings and structures that stood on the site in the Viking period. For me, the excitement was slowly tempered by the realization that I was chiefly responsible for looking after all this wood, both on site during excavation, then getting it lifted and stored safely, and probably then also conserving it permanently. There was little experience within the UK at the time on how to deal with waterlogged materials en masse after lifting but common sense told us that what we were going to need was a lot of tanks to store everything in, supported and packed to avoid damage and underwater. So we started to build tanks out of wood lined with plastic, then out of fiberglass, and finally for the larger timbers over a metre or so in length, we got the use of a huge outdoor concrete line wartime fire reserve tank on Clifton Aerodrome. There was an old wartime petrol-driven fire pump kept on site for emergencies that came in very handy when we needed to pump the thousands of gallons of water out of the tank for cleaning and maintenance or, much later on, for selecting timbers for conservation.

Miranda 9:01

You can hear more from Jim as well as other people who worked on the Coppergate excavation in that episode, so give it a listen - after this one, of course. So Jim Spriggs was instrumental in not only setting up the conservation lab, but also coming up with new techniques for conserving all of these organic materials. Can you tell us more about these conservation techniques, Ian?

Ian 9:20

Yeah, I think it's quite informative that Jim, I think, was the first member of staff appointed by Peter Addyman, who realized the importance of conservation so especially when you're working in an area with waterlogged deposits, so yeah, Jim was at the cutting edge and you know, I think he was mad enough to develop the acetone rosin process into into what it was at that time, he had the nerve to to deal with that. And then he started developing other techniques for treatment of leather using again polyethylene glycol, certain grade polyethylene glycol wax, which is a liquid at room temperature, and then it started to use glycerol again. I think it is a food preservative that's used in food processing. We now use that for glycerol. So Jim was instrumental in developing quite a few techniques.

Miranda 10:15

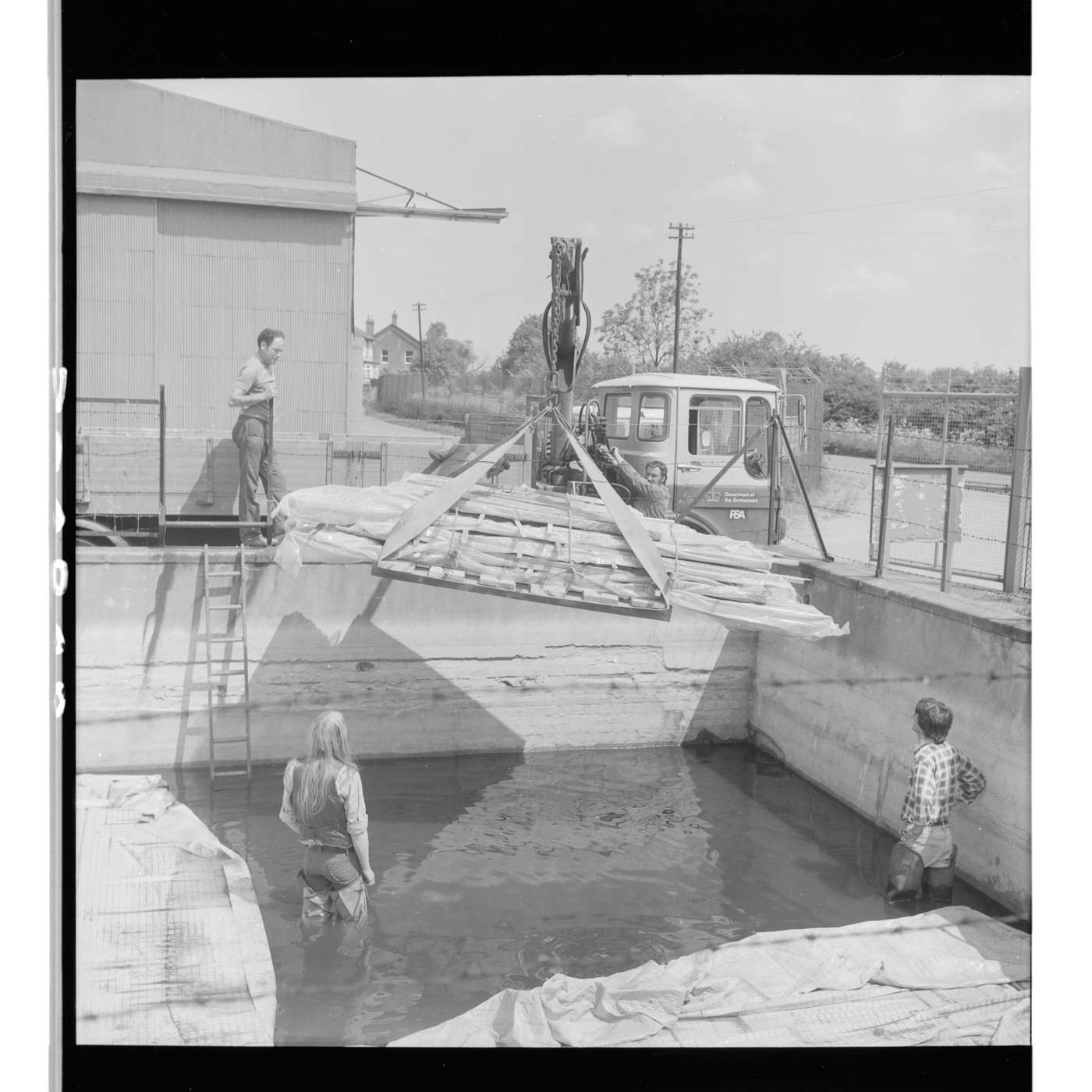

While researching this series, we’ve come across a lot of pictures of Jim in these big tanks where they were keeping these huge timbers and other artefacts wet. You can see some of these pictures on our Instagram - JorvikViking. We’ve even got a clip of him talking about these tanks.

Jim Spriggs 10:29

There was little experience within the UK at the time on how to deal with waterlogged materials en masse after lifting but common sense told us that what we were going to need was a lot of tanks to store everything in, supported and packed to avoid damage and underwater. So we started to build tanks out of wood lined with plastic, then out of fiberglass, and finally for the larger timbers over a metre or so in length, we got the use of a huge outdoor concrete line wartime fire reserve tank on Clifton Aerodrome. There was an old wartime petrol-driven fire pump kept on site for emergencies that came in very handy when we needed to pump the thousands of gallons of water out of the tank for cleaning and maintenance or, much later on, for selecting timbers for conservation.

Ian 11:17

Oh, gosh, yes. It was the fire fighting tank up at Clifton airfield. Yeah, which is no longer there, it's now housing estates. But Jim and I had to go in I think it must have been about '98, '99 because because they had sold off - it had been used as a grain store and they'd sold that off to the housing developers who then contacted us and said, "I think you got timbers in this tank." So Jim and I went in there and fished out all this old Coppergate timber, also timbers that have been recovered from the [York] Minster in the Minster fire in 1984. So you took those out, it wasn't very pleasant at all, just thinking just Jim and I in there, in the health and safety nightmare. We got everything, everything was in fantastic condition.

Miranda 12:09

Was there any sort of monitoring then in between when they were originally put in there?

Ian 12:13

No, I think Jim put them in the thinking he would be retired before he had to get them out, he had no intention of getting them out. It's just that we were forced into it because the land had been sold. So yeah, I mean, he just put them in there. Everything was double wrapped and labelled and you know, they were in really good condition when they came out.

Miranda 12:35

Incredible. So you know the conservation was working!

Ian 12:40

That's right. We also had a series of about 10 or 12 glass fibre tanks behind the art gallery. Again, that's now that's all been developed. It's all part of the art gallery. Now there used to be at the back of the art gallery in between the art gallery and the wall of the Abbey. There was a series of prefabs that was part of the Canadian Air Force buildings that they had during the Second World War. And there's a bit of land that he [Jim] had tanks on and I remember, it always used to get overgrown. And so when he'd say you got to go get these timbers out of tanks. He'd bring his machete he used in Belize. And he'd spend a day sort of chopping down the vegetation. Before we could actually get into the tanks. So my gosh, we had everything there from Coppergate right through to the Roman timbers from Queens hotel and such like. So we had quite a few of the old favourites in there.

Miranda 13:36

Wow, that's incredible. I love that. It seems especially right at the beginning. It was everything, like the space that we used and the equipment we used, was a bit begged, borrowed and stolen. You know?

Ian 13:47

It was yes, yes. Yes. Jim is great for - it was quite annoying actually at times, he could be coming to work or at lunchtime, you'd go past the skip, there'd be something in the skip and he'd pull it out and bring it in. Wouldn't it be nice to have some really brand new leather watch? But that's the way things are done in those times. Yeah, I mean, I mean, we would if we didn't have to buy something, if we could convince the developer to or whoever to let you know, donate something to us then. And that's the way we'd go.

Miranda 14:16

All the better.

Ian 14:17

Yeah, actually, our first freeze dryer, very small freeze dryer, I think that was donated to us from Hato, which was a Danish company and it was the Danish Queen. I think she asked them to donate a small freeze dryer to us.

Miranda 14:34

We've got some really great pictures of her in the conservation lab as well. And because she was, I guess, she was a friend of Peter Addyman's.

Ian 14:40

She was, yeah.

Miranda 14:41

But she studied archaeology as well. So she's properly investigating everything in all the pictures and stuff. I love that she donated something as well, or had it arranged. That's amazing.

Ian 14:50

Yes. That's, that's good. I mean, I think I don't know what the cost of freeze dryers was back in that day, but they're expensive now. So yeah, something that the Trust wouldn't be able to afford, so if they can get something given to them or, part-given then that was all well and good. That's how the lab was set up. It was mainly donations. And Jim's team's ability to find things in the skip.

Miranda 15:15

He sounds like a magpie.

Ian 15:18

His house is very tidy.

Miranda 15:21

So what do we do as far as conservation and things today that's different than what was done in the ‘70s?

Ian 15:31

I mean, obviously, we now use freeze drying more than say, solvents, because of health and safety issues. So it's a no no trying to do acetone rosin now, we've tried to do it as cold, but it doesn't work as well. So we've sort of knocked that on the head. And it's mainly freeze drying. But it's also I mean, the techniques that have been developed back in the ‘60s, in the ‘70s. We've now, you know, in our 40-50 years of view, so we know how these materials react, and we're beginning to see the problems with them now. So, you know, we've learned a lot and we still learn, but yeah, we tend to use the same sort of things. But yeah, I mean, you know, it's, it's the way conservation is actually very sort of - archaeology as well, you know, we're working in the past. So we take things slowly.

Miranda 16:24

Yeah, so today, YAT has become really well known for its wood conservation. So what other projects have come your way that you've gotten to work on as far as a conservation? You mentioned the Mary Rose?

Ian 16:35

Yeah, well, YAT hasn't done any work for the Mary Rose. But I worked for the Mary Rose, before coming up to York. So I was on the Mary Rose from 1982-86. Amazing. Yeah, that was fun. I mean, just before the ship came up. And that was a good time that, again, you know, where we were doing stuff that had never been done before in the country, but sort of looking at techniques that Scandinavian colleagues were developing.

Miranda 17:03

A quick aside, since we haven’t talked about the Mary Rose on this podcast before. The ship has its own fascinating history, but people mostly know it as the pride of the navy during Henry the Eighth’s reign. It was built in 1510 and sunk in 1545, and was a crucial part of several battles during that period. It was rediscovered in the 1960s, and marine archaeologists, who are trained to do excavations under water in places like the North Sea or the Thames River, carefully dug the ship out of the silt from 1979 to 1982 - which means it was going on at the same time as the Coppergate excavation. In 1982, the main section was carefully raised out of the sea and, of course, had to be conserved. Luckily for everyone, Ian was on-hand as part of the conservation team.

Ian 17:46

But yeah, we do quite a lot of work, external work, I guess one of the more challenging ones for me at the moment is the project I'm doing in Sydney in Australia, which is the Barangaroo boat. This was uncovered in 2018. Sydney Metro, who are sort of a government organisation, they're basically building a new metro system. So they were putting a new underground station in Barangaroo, which is on Darling Harbour and found the remains of this boat, which dates to about the 1830s, 1840s. In our time scanner, is not it's not very old. It's very good for the Australians, it's very significant because there used to be a law in Australia that you know, you weren't allowed to build boats, obviously, because of your background, and so this is thought to be one of the first non-indigenous boats that's been built , and it's all built out of Australian timber. In a very sort of rudimentary fashion and by people, I think have seen boat building going on, but they've never done it themselves, almost like I'd say [they were] sort of cabinet makers, because you get a lot of little wooden dowels and very small nails being used in the construction. So I got approached to sort of help them set up a wood conservation centre in Sydney and oversee the conservation. So I went over there in 2019. And then COVID hit, so I'm teaching these guys over there how to do wood conservation via Zoom and you're in the early hours of the morning and it's an interesting one, but got several projects over there now because they there's this Barangaroo boat, which is the most important one, and then there's what we call the Windsor boat, and about three not as significant or not as much as the Barangaroo boat. This is again, a similar project in that a new bridge at Windsor going over the river, which was flooded actually a few weeks ago, had horrendous rainfall. So they were flooding and this new bridge they built was under water.

Miranda 20:00

Sounds like a nightmare

Ian 20:01

Yeah. So, there's those ones as well which I'm now looking after as well so I hope to get that over there next year possibly.

Miranda 20:10

We’re definitely going to have to come back and hear about that! Thanks again for speaking with us, Ian.

If you want to learn more about the Mary Rose or the Barangaroo Boat, you can find links in our show notes.

Ian mentioned how the different drying techniques can change the look of the final conserved wood. You can come and see the difference yourself! The Jorvik Viking Centre re-opens the 17th of May 2021 - book your tickets now at JorvikVikingCentre.Co.Uk.

Stay tuned for our final episode of the season where we’ll discuss how Coppergate changed our understanding of the Vikings in the British Isles with our very special guest, Sarah Maltby, the director of attractions here at York Archaeological Trust.

That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast is an Audible Associate. Click the link in our show notes or go to audibletrial.com/vikingthing-21 to sign up for a free 30-day Audible trial. When you do, you'll get a free audiobook download, and you'll also be supporting your favourite Viking podcast. Even better, the audio book is yours to keep forever, no strings attached. This time we recommend....

“Ships from the Depths” by Fredrik Soreide. Researcher and explorer Fredrik Søreide tells us about the development of underwater archaeology since 1971, when a sea probe was designed to locate and raise deep-water wrecks in the Mediterranean. Along with examples of deep-water projects and equipment, this book describes the techniques that have been developed for locating and observing these sites, as well as excavation and removal methods unique to these special locations, far beyond the reach of scuba gear.

Thank you for listening to That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast. You can find us on Spotify, Apple podcasts, and anywhere you get your podcasts.

If you'd like to support That Jorvik Viking Thing, visit JorvikThing.com to make a donation. Don't forget to hit subscribe so you don't miss the next episode of That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast. Want to have a say in the future of your favourite Viking podcast? Click the link in the show notes to take a quick survey and let us know what you’d like to hear in future seasons! Transcripts and chapter markers are available on JorvikThing.Buzzsprout.Com.

That Jorvik Viking Thing Podcast is a production of the Jorvik Group and York Archaeological Trust. Researched by Miranda Schmeiderer and Ashley Fisher. Written and produced by Ashley Fisher. Sound designed and edited by Miranda Schmeiderer.