That JORVIK Viking Thing Podcast

In Viking times, a ‘Thing’ was a gathering; a place where leaders and warriors could meet and talk. In the 21st century, our ‘Thing’ is a virtual place where Viking academics and enthusiasts from around the world can come together to share knowledge.

Join Miranda and Lucas, from the JORVIK Viking Centre, as they delve into another fascinating topic about Vikings, archaeology, and more!

That JORVIK Viking Thing Podcast

The Coppergate Excavation: More than Just Vikings

So far this season (and this podcast), we've talked a lot about the Vikings that lived here in York and especially on Coppergate. But the history of Coppergate is more than just the Anglo-Scandinavians that lived here in the 9th and 10th centuries. This episode, we're talking again to Dr Chris Tuckley, Head of Interpretation and Engagement here at the JORVIK Viking Centre. You might recognise Chris from a previous episode, talking about how Yorkshire has celebrated the Vikings in the past 100 years. Today, though, he's telling us all about the Medieval residents of Coppergate and what they left behind for us to look at today.

Listen and enjoy, and please consider leaving us a 5 star review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen!

Miranda 00:00

In Viking times, a "thing" was a gathering, a place where leaders and warriors could meet and talk. In the 21st century, our "thing" is a virtual place, where history academics and enthusiasts from around the world can come together to share knowledge. I'm your host, Miranda Schmeiderer, and this season, we’re doing a deep dive into the Coppergate excavation. So hold on to your helmets for this episode of That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast!

Miranda 00:34

We hope you’re enjoying our deep dive into the Coppergate excavation, the dig that put York - and Jorvik - at the centre of Viking archaeology here in Britain. Last week, we talked to Rachel Cutler, who told us about some of the star Viking finds. This week, we’re talking to Dr Chris Tuckley, Head of Interpretation and Engagement from here at the York Archaeological Trust. He’s going to talk about some of the spectacular Medieval finds from the dig, and we’ll learn a bit more about what was found from other time periods as well, from the Romans all the way up to the Victorians. So Chris, we know that Coppergate was used by more than just the Vikings. What do you have for us today?

Chris 01:12

So today we're looking at medieval Coppergate. It's not a period that we look at in any great detail at the Jorvik Viking Center. And where we are, in particular, looking at some of the most interesting small finds to come out to the medieval levels at Coppergate. The period that we're considering is known by the archaeologists who worked on the Coppergate dig as period six, and that covers a period from the latter part of the 11th century up to the early post Medieval period or the early modern period, which falls around about the 16th century. And whereas we think of the Anglo Scandinavian, or the Viking levels at Coppergate being very rich in finds, and also in the sort of dark soils, the organic material that's very, very well preserved for the ninth and 10th centuries, actually, for the medieval period, It seems that the the people who were living along Coppergate cleaned up their act. And there were better systems for taking away waste materials and tidying up so you don't get the same piling up of rubbish. And the same use of open pits for using as toilets and for rubbish disposal. So actually, there's less surviving from those later levels, than there is from a comparable length of time earlier in the medieval period. And actually, according to what I've been looking at, there were no remains surviving In terms of the street frontage of Coppergate. There were some buildings or the remains of some buildings found further back from along those slots.

Miranda 02:54

That’s so fascinating! I had no idea that we found anything, really, other than things from the Viking period.

Chris 03:00

It's not publicized really, is it? I mean, when we think about the Coppergate dig, we think almost exclusively about the Viking levels. And for anyone who looks into the material that was recovered at the Coppergate dig, you can quickly see that the entirety of York's history is represented within the archaeology there from the Roman period right up to the Victorian period, really and later than that, but we always concentrate in terms of the interpretation that we do at the Jorvik Viking Centre on the Viking levels and so it's the Viking archaeology that the site is known for.

Miranda 03:43

So what’s our first Medieval find from Coppergate?

Chris 03:47

We can consider first the ring that was found, a real luxury item made from very high quality gold, a better quality than 18 karat gold as I understand it. So a really refined item and set with a single pearl and four garnets so presumably this fell off someone's finger at some point during the mid 13th century and landed in a pit - it was found at the side of a pit next to a cobble path. So some important wealthy person no doubt has been ambling along and they've lost this ring and this must have been a terrible loss that must have been greatly regretted.

Miranda 04:34

Unfortunate for them but lucky for us!

Chris 04:37

Absolutely. Lucky for us we now have it to look at the pearl has been looked at. It's probably a freshwater pearl. And the ring itself is set with it's got an inlaid pattern in a darker colour. And analysis has shown that this is niello that has been used to decorate the ring. So this is a real luxury item from the medieval period found at Coppergate and one that isn't particularly well known.

Miranda 05:04

That sounds absolutely gorgeous. So what else was found?

Chris 05:08

So the next artefact is a slightly more practical item, it is part of a box. And it's thought that it's the lid of a box. It's about 55 to 60 centimetres long, about 27 centimetres wide. And it's woven from willow. So it was found in quite a sorry state had been squashed out of shape by the way to the soil that was on top of it. But it was recovered together with some old shoes from an excavated cellar within the remains of a timber framed building. It was lifted en masse out of the soil, so it was block-lifted and taken straight to the lab. And it stands as a unique example of skilled woodworking and basketry techniques of the 13th or 14th century. Now, I guess it would be quite difficult to put something like this on display because of its size, and its probable fragility as well, which again, is probably why it's not, it's not a well known piece from the Coppergate site. It has a willow frame with jointed corners, and there is space between the slats that were filled with tightly packed woven willow rods, and there's no metal at all within the lid. And even the hinges are probably willow rods. So the level of basket working skill and carpentry skill that's going to this construction is significant. And nothing of the rest of the box remains; it may have been constructed out of wooden planks. No other lid of this type is known in England or Europe. And it's it's guesswork as to what a box like this with a wickerwork lid would have been used for maybe it was like a laundry basket of the kind that we might recognize in our own homes today, which obviously are often constructed of, of wickerwork.

Miranda 06:56

Of course, I have a similar one at home. This sounds vaguely familiar though.

Chris 07:01

Well, there is another example of a box lid found at Coppergate. This one is more well known and currently on display at Jorvik. It's from the Viking period. And it is a lead or at least decoration for a box lid made from pigs rib bones that have been decorated with incised lines.

Miranda 07:24

It’s one of the other star finds at Jorvik, that’s right. Interesting that we found two really unique and completely different box lids at the same site. So what else do you have to share with us?

Chris 07:35

This is the find that my colleagues are most excited about. It's probably the most perfectly preserved medieval bucket in Britain, is how it's been described. And it was found at the bottom of a contemporary well at copper gate. And the well itself was lined with a barrel or cask. So similar techniques used to construct both the buckets and barrels in that period. Remarkably, both the wooden bucket and its iron chain and fittings have been preserved. So perhaps the chain broke at some point as water was being drawn, or it was accidentally dropped. And it remained buried for 600 years or thereabouts until the archaeologists found it. And when you look at the photographs of the bucket, it looks as good as new. It looks as though you could pick it up and use it to draw water today. looking closely at the bucket. The conservation team found that it was made of nine oak uprights called staves that were bound together by three iron bands. A handle was fixed through holes that have been pierced in two longer staves whose rounded ends extended beyond the rim. So they do stand proud of the rest of the structure of the bucket. And then these holes have been reinforced with iron plates to take the weight from a chain which was attached to the handle using a swiveling mechanism. So quite a piece of engineering thought to be of an early 15th century date. And that is based on pottery that was found with the bucket and on the location of the well in relation to other layers on the site. Who would have made a bucket of this kind Well, it could have been a Cooper Cooper's we think of making barrels particularly for storage, probably working outside the city in Woodland areas. So they are close to their raw materials, and traveling into town to sell their items in the markets of York.

Miranda 09:37

Don’t forget to check our Instagram at JorvikViking, where you can see pictures of this bucket - it really does look like you could just pick it up and use it. Are there other everyday objects that were found from medieval Coppergate?

Chris 09:49

A minor and slightly more modest find from Coppergate is a fragment of a piece of pottery. So it's a ceramic item, and it's been suggested that it is part of a plant pot. I don't know I'd probably never imagined that people in the medieval period used plant pots, but of course they did. It stands to reason, doesn't it because gardening went on in the medieval period just as it does today. And no doubt people even in cobbled yards would have had reason to grow plants either for practical purposes, or for decoration. And also it's quite possible that cut flowers could be sold as well in the city. So no doubt horticulture is going on in the medieval period. It's about 100 mil wide. It's not a fancy piece at all, but it does have part of a human face within the decoration between two of the handles, and combed wavy lines. And it's glazed both inside and out.

Miranda 10:54

Of course. It does make sense that they’d be using plant pots for gardening, just like we do today.

Chris 10:59

It stands to reason, doesn't it? Yes. And when I was saying what I was saying, I did have the courtyard at Barley Hall, our reconstructed medieval townhouse in my mind's eye as I was thinking about that. And the way in which we often have little pots with plants sort of flanking the door into the admission area of Barley Hall.

Miranda 11:16

I’m never going to look at that courtyard quite the same again. You’ve got something a bit on-theme for Jorvik for our next medieval artefact, is that right?

Chris 11:23

The toilet seat, or seats from Coppergate, we did use to feature an image of one of the toilet seats inside the Viking Centre. So I remember when I was working in front of house at Jorvik. So this is back in 2004-2005, that sort of period, we did have an image in the sort of the orientation area, which was made to look a bit like a dig site or the outside of the dig site, we did have a picture of one of these toilet seats on display, but it doesn't strictly belong to the Viking period. It's thought to be of the 12th century. And there are two examples. And you can tell exactly what it is just by looking at it. It's a thick Plank with a bottom shaped hole right in the middle of it. So you can imagine exactly what they were used for. Essentially, they were mounted over a pit and then you could sit on them exactly as you would any other toilet seat and do exactly as you would while sitting on any other toilet seat, I don't need to go into too much detail. So they're both made of thick oak planks about a meter in length. One of the names that is sometimes used to describe the toilet in the medieval period is a garderobe, and one of them was actually found inside a pit. And perhaps it's the pit that it was used over. And maybe the seat has tumbled into it at some point. And that's how it's been lost and how it's working life has ended. They were conserved in the same way as the other historic timbers from Coppergate. And I believe in a future episode, you'll be hearing more from our conservation team about the measures that were taken to conserve the wooden items from Coppergate. The toilet seat in the medieval period, it doesn't have to be what's known as a single holer, you can have a triple holer as well, it's three holes in a row. So presumably you are increasing the capacity of your toilet so it can be used by multiple visitors in one sitting and you're in no danger of being lonely. You can, you can sit there and take care of business in company possibly if you're sitting in the middle with a friend either side of you. So the mind boggles really doesn't it.

Miranda 13:28

I can’t say that I’d be excited to use a toilet that was quite so communal, but to each their own! We’ve got something a little less gross now but just as interesting. It looks like a triangle piece of leather with a thin strap attached to it. What can you tell us about this artefact, Chris?

Chris 13:43

There is an item that's been identified as an archers bracer. And now I don't know a great deal about archery. But I understand that this is worn on the inside of the arm, so that when you draw the bow string and then release it, it doesn't scrape painfully along the inside of your arm that sort of tender, tender bit of skin on the inside of your arm next to your wrist. It's an example of recycling. It was found amongst lots of leather off cuts and waste and other bits of recycled leather material. And it seems at an earlier point in its life to have been a shoe specifically a long shoe known as a poulain type of shoe fashionable in the later 14th century sort of pointy toed variety with a toe that could sometimes extend up to 100 millimetres beyond the tip of the big toe. So these are really showy pieces of footwear. And if you look closely at the bracer you can see that enough of the original shoe remains to show that it was fastened with a buckle and loop over the instep. But the way in which it has come down to us is in its recycled form as an archers bracer.

Miranda 14:54

Between recycling items like this and also using less open pits like you talked about before, it sounds like medieval Coppergate was a pretty clean, eco-friendly place. But our next artefact is something a bit fancier. Can you tell us about the ampulla, Chris?

Chris 15:09

The ampulla is - well it belongs to a kind of find that's found fairly commonly in medieval sites throughout England. An ampulla is a small vessel made of pewter or tin normally roughly flask shaped and it would at one time have held liquid contents possibly water or oil, specifically holy water or holy oil that has at some point come into contact with a saint or a saint's shrine. And these were picked up or purchased by pilgrims. So a pilgrim going to one of the important pilgrimage sites would often collect souvenirs to either then act as a talisman or a focus for prayer and other kinds of devotional activities. Ampullae, which is the plural of ampulla, were a way of carrying away some holy water from a shrine that you have visited. And in York, the principal shrine in the pre reformation period was that of St. William, who was a 12th century Archbishop of York who was canonized as a saint. And you can visit bits of his shrine, certainly it was broken up just ahead of Henry VIII's visit to the city and in the 1540s. And lumps of it ended up hidden in various parts of the city. But those bits that have been recovered and could be pieced back together, show that it was a really substantial structure. There were several shrines that stood on that site. It was the latest of those that was broken up before Henry VIII visited, and you can see bits of it on display in the Yorkshire Museum. Many ampullae and pilgrim badges associated with Thomas Beckett, who is the saint's shrine you visit at Canterbury, which is the premier pilgrimage site in England, lots of those have been recovered. But only two associated with William that have been found at Coppergate seem to have survived. Although no doubt, lots of these would have been made in large numbers in York. The figure of the Archbishop who appears on the ampulla is probably Archbishop William. And there are also figures that have been identified as St. Peter and Paul, so two New Testament saints who often appear in company, in combination. And of course, York Minster is dedicated to St. Peter. And that's a long standing dedication as well.

Miranda 17:38

I didn’t even realise that we had a saint from here in York! Our final one, I think, is one of your favourites. Can you tell us about the brazier?

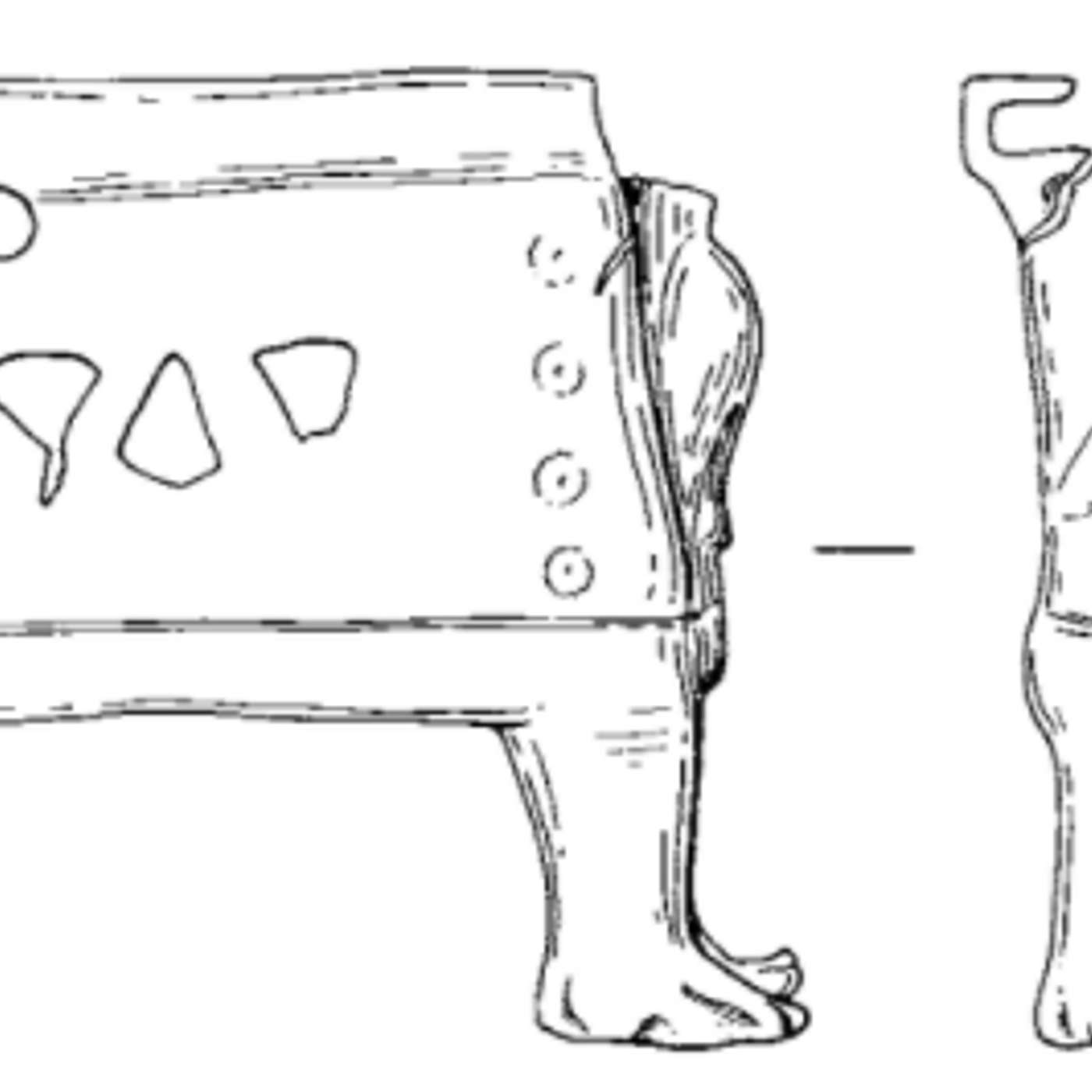

Chris 17:47

The brazier wasn't actually found at the Coppergate site, which is normally given the address 16 to 22 Coppergate, it was found in the much wider area somewhere in that much wider area covered by the watching brief. And that was run by your archaeological trust around the time of the Coppergate excavation. So it's not an item that I don't think many of my colleagues are very familiar with this particular item. But it's one that really, really stood out to me because I'm often thinking about our reconstructed medieval townhouse Barley Hall, and it's got very, very high ceilings, and it must have been very difficult to heat the rooms during the medieval period. It's cold during the 21st century, so in the 14th and 15th centuries, you know, it must have been chilly and difficult to warm. The high ceilings really were an expression of high status, if you could have a dwelling with very high ceilings, it meant that you could afford to burn lots of fuel to keep your house warm. But how do you do that in an upstairs room, in a bed chamber? You can't have an open half as we do in the Great Hall of barley Hall. So instead you need something probably portable, and also that's going to be self contained and safe from a fire safety point of view as well. So if you're setting it up on a planked floor, it needs to stand clear of the floor and burn away. And this is when you get something like a portable brazier. And this is what was found in the 15th to 16th century dumped soil and it's decorated as well. It's decorated with a cast four legged animal with a large snout and tail, while one of the longest sides of the brazier has got some simple open work and a large perforation as well as stamp ring and dot motifs. Both of the less intact sides seem to have had open work within them as well. So it's a piece that I think deserves to be better known. The interpretation of it given by the archaeologists who examined it was that it's either a brazier or a food warmer, but certainly the kind of item that you might have found possibly in a higher status medieval household. I'd love to get to know it better, I'd love to see something like it reconstructed and installed at Barley Hall.

Miranda 20:02

I’d love to see something like that at Barley Hall, too. Thanks for telling us about these fascinating finds, Chris!

As we said at the top of the episode, there were also some Victorian and Roman finds that were excavated. Most of the Victorian levels were scraped away to get to the earlier levels and so not much was found there. However, there was a pit full of Victorian dental casts in one section, which leads us to believe that a dentist was working on Coppergate for a time.

Miranda 20:29

At the other end of the spectrum, the Roman levels were turning out to be just as interesting as the Viking levels. In fact, it seems that there was a large Roman cemetery here at Coppergate. We don’t actually know how large the cemetery was, as it extended past the excavation site on the north-west and south-west side. We do know that it’s one of three Roman burials on this side of the fortress, which was located where York Minster is today.

We found six burials, known as inhumations, and one empty grave. Only half of the graves were buried with anything. One burial had glass beads and a jet finger ring, while another had a coin placed beneath its skull. A third burial had a coin placed next to one leg and two pairs of hobnailed shoes next to one of the feet. The leather from these shoes had rotted away, unfortunately, but the nails from the bottom of the shoes were left behind in the soil, leaving a perfect bootprint for archaeologists to find.

Miranda 21:20

As always, check out our Instagram at JorvikViking to see pictures of these hobnails as well as some of the other finds we talked about today. Special thanks to Dr Chris Tuckley for being our guest today, also thanks to Max O’Keeffe for his help with the Roman burials research.

Next episode, we’ll be talking to Ian Panter, Head of Conservation at York Archaeological Trust. He’s going to explain to us the science of the soil - what exactly about the soil at Coppergate was so special that it preserved all these amazing finds? He’s also going to tell us about the conservation work done on these fantastic finds to preserve them for future generations.

Don’t forget, the Jorvik Viking Centre re-opens the 17th of May 2021 - book your tickets now at JorvikVikingCentre.Co.Uk. Come see where it all happened and look at these amazing finds for yourself!

That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast is an Audible Associate. Click the link in our shownotes or go to audibletrial.com/vikingthing-21 to sign up for a free 30-day Audible trial. When you do, you'll get a free audiobook download, and you'll also be supporting your favourite Viking podcast. Even better, the audio book is yours to keep forever, no strings attached. This time we recommend....

“The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England” by Ian Mortimer. Have you ever worried how you’d survive if you travelled back to the fourteenth century? Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. Ian Mortimer shows us that the past is not just something to be studied; it is also something to be lived. He sets out to explain what life was like in the most immediate way, by taking you right back to the Middle Ages.

Thank you for listening to That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast. You can find us on Spotify, Apple podcasts, and anywhere you get your podcasts.

If you'd like to support That Jorvik Viking Thing, visit JorvikThing.com to make a donation. Don't forget to hit subscribe so you don't miss the next episode of That Jorvik Viking Thing podcast.

Want to have a say in the future of your favourite Viking podcast? Click the link in the show notes to take a quick survey and let us know what you’d like to hear in future seasons! Transcripts and chapter markers are available on JorvikThing.Buzzsprout.Com.

That Jorvik Viking Thing Podcast is a production of the Jorvik Group and York Archaeological Trust. Researched by Miranda Schmeiderer, Ashley Fisher. Written and produced by Ashley Fisher. Sound designed and edited by Miranda Schmeiderer.